No rich country has a rate of maternal death (and near-deaths) comparably high to the US. The blame has been placed largely on how the US treats pregnancy and related emergency issues, but new data on deaths across the US (pdf) released by the country’s Centers for Disease Control (CDC) suggest otherwise: there are systemic issues causing American women across all age groups, and particularly younger women, to die earlier.

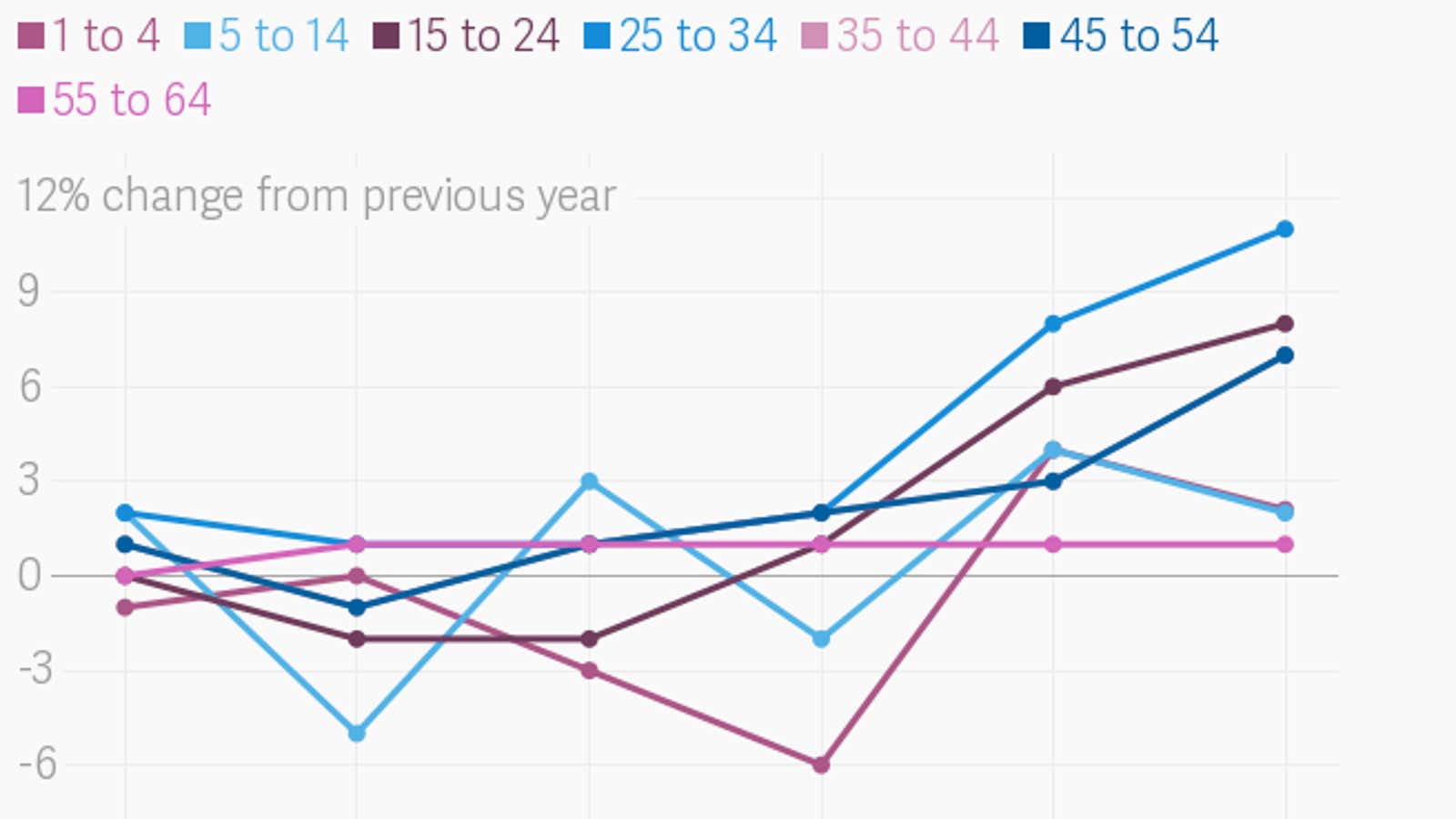

From the 1950s through the 2000s, the mortality rate for women living in the US declined steadily year over year. But, as the most recent CDC show, from 2010 to 2016, that trend has reversed—especially for women younger than 54.

Following a similar pattern, maternal death rates in the US declined steadily for most of the 20th century, then started going up again, reaching alarming levels in the early 2000s.

In an analysis of the new CDC data for STAT, maternal health experts Neel Shah and Eugene Declercq, of Harvard Medical School and the Boston University School of Public Health, respectively, note that it now seems maternal mortality may have be a “canary in the coal mine,” announcing a larger emergency on the way for the overall health of US women.

We tend to think of maternal mortality in terms of emergencies. But according to the CDC, between 1987 and 2013, maternal deaths caused by emergency conditions such as hemorrhage and infection dropped 60%, while pulmonary embolism and amniotic fluid embolism decreased about 20%. On the other hand, maternal deaths linked to chronic diseases are up: The incidence of cardiovascular conditions has risen more than 300%, cardiomyopathy by 100%, and strokes (which can be linked to chronic conditions like high blood pressure and obesity) have by 83%.

About 12% of women of reproductive age (between 15 and 44 years old) in the US don’t have health care insurance. These women are entitled to Medicaid coverage during pregnancy and for six weeks afterwards, but often, the first time they’ve seen a doctor in years is when they pregnant, which is too late to address any chronic condition. Then, even with Medicaid, they typically see the doctor only once after delivery. This is why the vast majority of US women who die of pregnancy-related causes don’t do so on the day they give birth but in the months before and after delivery, when they are more likely to be hit by the effects of chronic diseases—including mental health issues—exacerbated by pregnancy- and postpartum-related physical and mental changes.

Meanwhile, between 2010 and 2016, death rates due to chronic conditions—such as liver disease and cirrhosis, suicide (a symptom of mental health issues), and diabetes—increased for women between 15 and 44 years old. The fact that young women are dying more often from chronic illness suggests they are paying the price of falling through the cracks of the US health care system. Older women, among whom death rates have steadied in recent years, are more likely to access medical attention, and therefore may paradoxically be healthier.

It’s also why efforts to reduce maternal death by through addressing flaws in the the ways hospitals deal with emergencies and by improving the quality of childbirth have not done enough to stave the mortality rate trends. Instead, as Shah and Declercq argue, we need to deal with the problem of chronic illness and lack of long-term health care for women. In a country with a health system that offers only sporadic care for women, mortality rates across the board are only going to continue to rise.