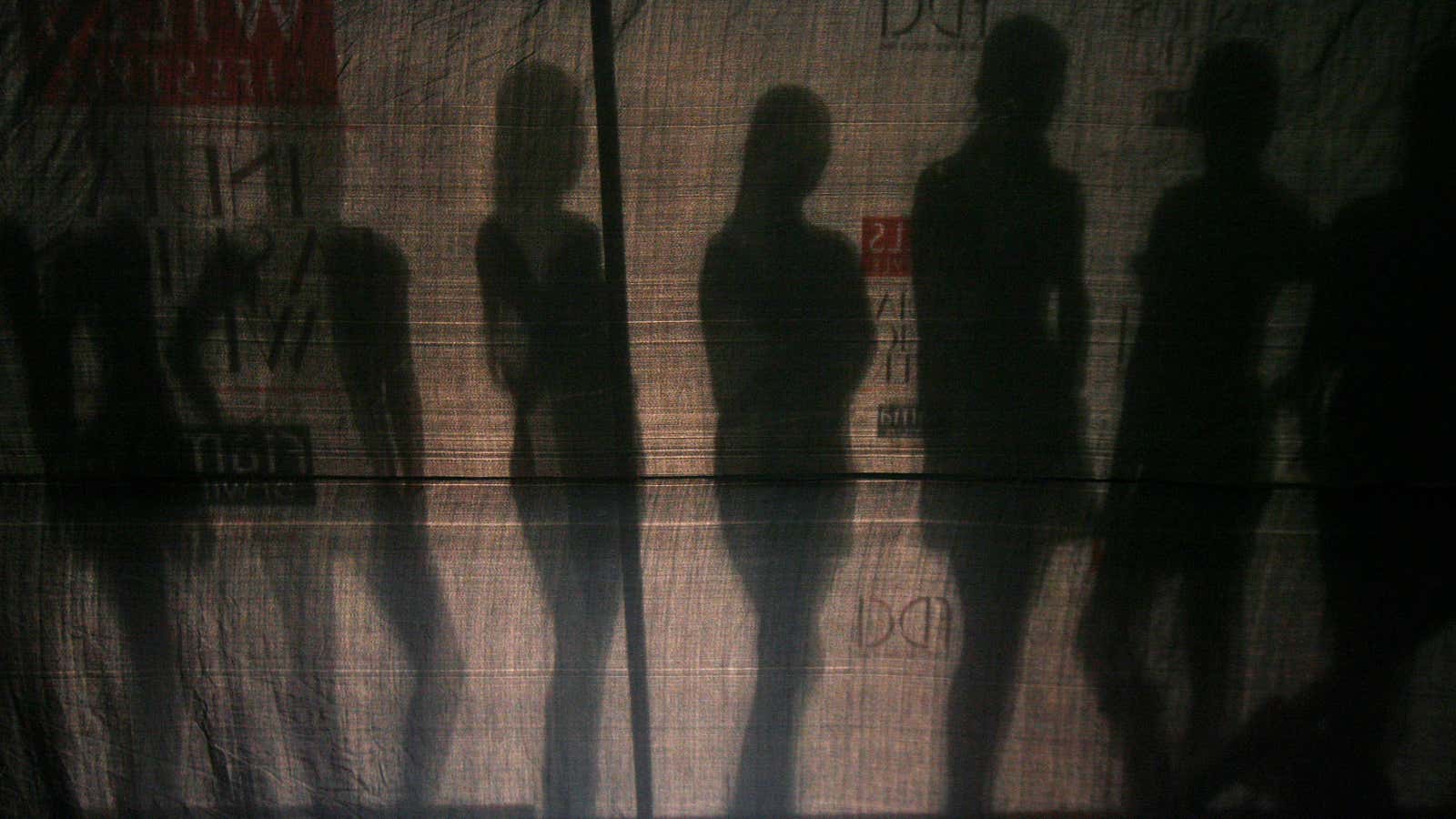

The #MeToo movement has arrived in India, and it is the media and entertainment industry that’s getting a massive shake-up.

While several women are coming out with their stories on social media, a leading Bollywood production house has been dissolved following allegations of sexual assault made against one of its four partners.

On Oct. 06, a former crew member of Phantom Films, founded by filmmakers Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane, Vikas Bahl, and Madhu Mantena, accused Bahl of molesting her in May 2015. Bahl is best known for his 2014 blockbuster film Queen, widely praised for its feminist theme.

In an anonymous interview to Huffington Post, the accuser said that Bahl barged into her hotel room and forced himself on her after a party in Goa. When she resisted, he dropped his pants and masturbated. Over the next few months, he made several more advances at her, until she quit in January 2017.

A day before the interview was published, and three days after Huffington Post sent out a questionnaire on the issue to Phantom Films, the partners announced they had dissolved the firm.

Bahl’s, however, is only the latest in a string of relatively high profile names to be outed over the past few days by women in India who have allegedly been subjected to sexual misconduct in the course of their professional duties over the years.

It all started when a few weeks ago, Bollywood actor Tanushree Dutta raised allegations of sexual harassment against Nana Patekar, her co-star in a 2008 film.

Now, the country’s news media industry, in particular, is convulsing, with at least 12 female journalists coming out with stories of harassment, often at the hands of their male colleagues.

The ugly side of news

The wave was set off by writer Mahima Kukreja, who on Oct. 04 accused comic Utsav Chakraborty of sending her unsolicited pictures of his genitalia. Following her revelation on Twitter, more women tweeted saying he was a repeat offender.

Kukreja’s tweets evidently opened the floodgates, as now allegations are flying thick and fast against several senior and well-known industry figures.

On Oct. 05, for instance, Anoo Bhuyan, a reporter at news website The Wire, accused a fellow reporter of the Business Standard newspaper, Mayank Jain, of making unsolicited sexual advances. Two women journalists replied to Bhuyan’s tweet, saying they had similar experiences with him.

Business Standard has reportedly set up an internal investigation committee to probe the accusations.

Soon after Bhuyan’s tweets, journalist Sandhya Menon tweeted that KR Sreenivas, resident editor of the Hyderabad edition of The Times of India newspaper, had made an unsolicited advance at her in 2008.

Menon also posted screenshots of texts from three other women who had worked as interns at the paper and said they were sexually harassed by Sreenivas during and after their internships.

“If one person comes out it emboldens the others,” said Ammu Joseph, senior journalist and co-founder of Network of Women in Media, India, an association that provides resources and support systems for women journalists. “It almost feels like an obligation. If one person has outed somebody, then other people feel it’s better that they also come forward so that the one person is not victimised.”

While Jain has not made any public statement on the allegations, in a reply to Menon on Twitter, Sreenivas said he will submit to an investigation.

However, Menon told Quartz she isn’t convinced that the investigation will yield any result.

She said she had reported Sreenivas’s alleged misconduct to The Times of India’s committee against sexual harassment, but “the woman who headed it told me she knew Sreenivasan for a long time and it’s unlikely he’d do something like that.”

Last October, in the first rumblings of #MeToo in India, law student Raya Sarkar had created a public list where women could anonymously accuse men associated with Indian academia of sexual misconduct.

Menon’s tweets have similarly turned into a thread of sexual harassment accounts after women journalists texted her their stories. She has agreed to not disclose the accusers’ identities.

But at least two women who earlier chose to stay anonymous have now come out after their stories were backed by other women’s experiences. One of them is journalist Avantika Mehta, a former reporter at the Hindustan Times newspaper.

Mehta had accused Prashant K Jha, national political editor at the paper, of making sexual advances at her through text messages even though she made her discomfort evident. Mehta said she would try “to not piss him off while he says he wants to hit on me,” as it could have “shit repercussions for my career.” She quit the paper in 2016, after two years of joining it, “tired of its boys’ club.”

The Hindustan Times management has said an investigation against Jha will be launched, and that action would have been taken had Mehta reported his misdemeanour immediately.

Menon, meanwhile, also accused Gautam Adhikari, then editor-in-chief of the Mumbai edition of the DNA newspaper, of kissing her without her consent.

Adhikari said he is now retired from journalism and has no recollection of the incident.

Sonora Jha, a journalism professor at Seattle University, who was the chief of the metro bureau at The Times of India’s Bengaluru edition while Adhikari was executive editor, said she too had been sexually assaulted by him. “Later, when I told my resident editor, I was told that Adhikari had asked him to ‘sideline’ me on the job. The Times Of India asked him to leave but I believe they brought him back.”

On the job

Several female journalists have also spoken out about incidents of sexual misconduct by people outside the industry, whom they interacted with at a professional level.

“In the old days, you didn’t want to make too much of a fuss because you were fighting for the right to report on politics and hard news,” Joseph said. “You didn’t want to call attention to the fact that you’re a woman and therefore you have some additional vulnerability. You felt that that would go against you and you would be put back on soft stories.”

Not much seems to have changed since then.

Nikita Saxena, now a journalist at The Caravan magazine, said that an advertising executive she had visited for an interview kissed her on the cheeks without her consent. “What kind of power does a journalist have over a source on the beat they report on? None,” she tweeted.

Journalist Neha Dixit said editors can also be complicit in such cases, adding that a female editor “had told me when a source puts his hand on my thigh and gives me information, I must put up with it.”

One female journalist has also anonymously accused best-selling author Chetan Bhagat of making sexual advances at her, sharing screenshots of their conversations.

Bhagat issued an apology on Facebook. “…I am really sorry to (the) person concerned,” he said. “Maybe I was going through a phase, maybe these things just happen, or maybe I felt the person felt the same too based on our conversations (which I don’t need to repeat here). However, it was stupid of me, to feel that way and to even share that with her.”

Due process

The wave of allegations has spurred questions over due process and the effectiveness of social media in India.

“On social media, there can only be accusations and calling out. There’s a certain value to that, but there has to be something more,” Joseph said. “There are grey areas in anything to do with gender relations. Some of this does need to be discussed with a little more nuance.”

Indian law requires workplaces to have a committee against sexual harassment headed by a woman employee. However, their efficacy and consistency in handling such cases are questionable. Menon’s circumspection at The Times of India’s new probe against Sreenivas is a case in point.

“We need to make our institutions more accountable,” said Minu Jain, an editor at the news agency Press Trust of India. “Each organisation needs to look within itself to see how they’ve dealt with complaints like this and how they plan to deal with them in the future.”